Folly Beach lawyer recalls defending Pee Wee Gaskins, South Carolina’s most notorious serial killer

By Jenny Peterson | Staff Writer

Local newspapers called him “the meanest man in South Carolina.”

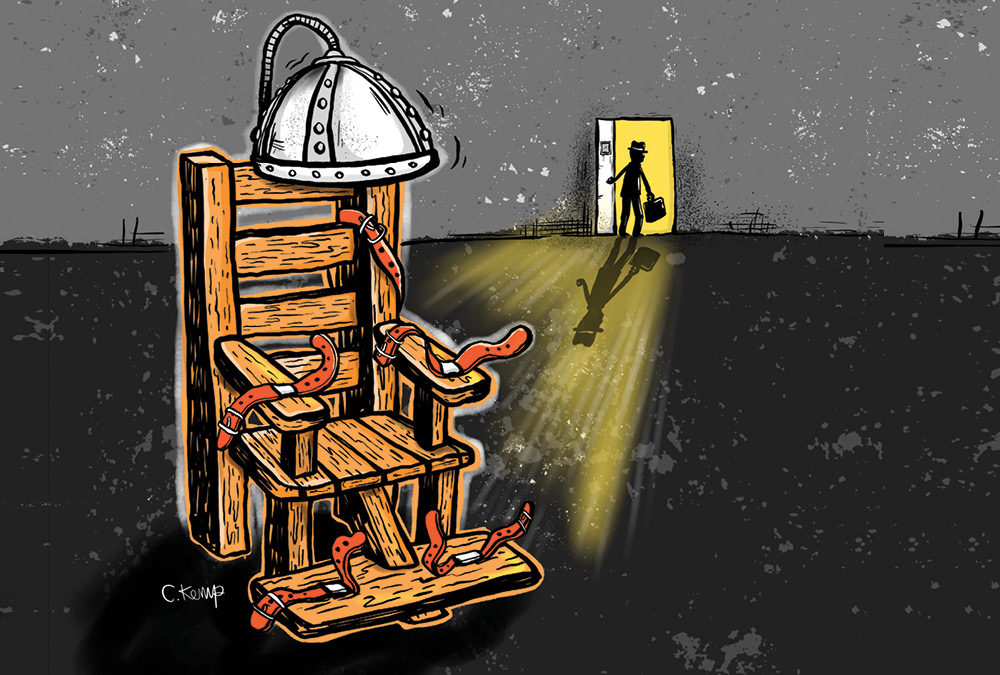

By the time he was executed by the electric chair in 1991, Donald Henry “Pee Wee” Gaskins had told law enforcement that he had murdered at least 20 people between 1953 and 1982.

He was nicknamed “Pee Wee” because of his short stature.

He was only 5’2” tall, but don’t let that nickname fool you: he was one of the most prolific murderers in South Carolina history.

The defense lawyer for this South Carolina serial killer?

Folly Beach lawyer Grady Query.

Query spent 12 years conferring with the notorious killer. Query describes Pee Wee as an intelligent, polite, and completely unremorseful person. Pee Wee admitted to — and then attempted to justify — every murder in which he was accused of in the days leading up to his execution.

“He told me the number was over 50 murders,” Query said.

His first murder conviction was for one of six people found in shallow graves in Prospect, SC, where he grew up, about two hours north of Charleston.

The victims included criminal associates, an ex-lover, and her new boyfriend. When these bodies were uncovered, Pee Wee was living in North Charleston.

During his lifetime, Pee Wee was also was accused of killing his niece; a young North Charleston woman and, separately, a two-year-old girl.

While on death row at the Central Correctional Institution in Columbia, Pee Wee committed his final murder, that of a fellow death-row inmate. It was part of a murder-for-hire plot. Gaskins smuggled in plastic explosives and fashioned a plastic bomb to look like a walkie-talkie.

The victim was told to walk several yards away and press the talk button in order to see how the walkie-talkie worked. The unsuspecting inmate pressed the button with the instrument next to his ear; the explosion blew his head off.

In 1975, Query represented Pee Wee’s associate, James Judy Knoy, who was implicated in two of the murders of victims found in the shallow graves.

Knoy eventually pled to accessory after the fact and was given three years in jail. Query had seen Pee Wee during that trial in Florence County and was in contact with Pee Wee’s public defender.

“The first time I saw Pee Wee was in court,” said Query. “He was a tiny little guy and very polite, very well-spoken for someone with no education. He knew about Folly Beach; he had stories about Folly, about coming out to the old pier to see Fats Domino perform.”

At the end of the trial, Pee Wee and accomplice Walter Neely were charged with all six murders.

“Pee Wee’s mother was at the trial, she was very stoic,” Query said.

After the trial, Pee Wee’s sister approached Query about filing her brother’s appeals. She paid him a retainer and Query got to work.

“He was ready for the fight, and he denied doing it at the time,” Query said.

Another murder came to light in another county during the appeals process.

It concerned the killing of a wealthy farmer in Sumter County in a murder-for-hire plot. A judge appointed Query as Pee Wee’s attorney.

“The judge said, ‘You already know about these cases, so we don’t need somebody else to catch up. So, now you are representing him in Williamsburg County,’” Query recalls.

After a lengthy trial, Pee Wee was sentenced to consecutive life sentences. He was placed on death row for “everyone’s protection,” according to Query.

That plan backfired when Pee Wee was hired to kill the death-row inmate. That’s when Pee Wee was sentenced to death.

“After all the appeals were over, and he had killed a guy in prison, and we were waiting for the death penalty, “I said, ‘Pee Wee, why don’t you tell me what really happened,’” Query recalls.

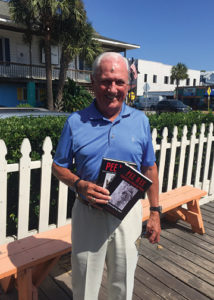

These stories and more are documented in an extensive two-part novelized crime series that Query wrote entitled, “Pee Wee: Serial Killer or Homicidal Maniac” Volume 1 and II.

“I talked to him during those last years of his life with the full intention of writing this book. I had him tell me all about his childhood, and all about his criminal history. We went through all the murders,” Query said. “He was a true sociopath, the only rules he acknowledged were his own and if you broke his rules, your life might be the price.”

Chilling accounts of conversations with Pee Wee included his rationalization about his killing sprees.

In his book, Query declares, “Pee Wee was a killer apparently devoid of conscience.”

Another book about Pee Wee’s life was also published. While on death row, Pee Wee told his life story to a journalist. In those memoirs, published posthumously, Pee Wee confessed to dozens of what he called “coastal murders” of hitchhikers throughout the Southeastern US Coast.

Query denies the validity of those claims.

“I believe his ‘coastal’ murders were contrivances that he intended to be his final finger in the eye of law enforcement,” Query writes in his book.

MAKING OF A MURDERER

Pee Wee Gaskins was born in 1933 in Prospect, S.C., in Florence County. He was the youngest child to an unwed mother. He spent much of his childhood and adolescence in court for a host of crimes including sexual assault and numerous burglaries. Pee Wee’s life was defined by an abusive and neglectful childhood, Query writes.

His first real run-in with the law was in 1946 at age 13. While Pee Wee was loading up items during a home break-in in the nearby town of Florence, a girl from his school came home and caught him, Query writes.

She picked up an ax in order to chase him off, but he took the ax and attacked her, nearly killing her, Query writes. Pee Wee was sentenced to the South Carolina Industrial School for Boys in Florence until he was 18 years old — the maximum sentence for a juvenile.

The correctional school failed to straighten him out. In order to “establish himself,” Pee Wee attacked a larger boy at the school with a hammer blow to the knee and then bit off his ear for good measure, Query writes.

Pee Wee escaped the correctional school four times, and at age 15, joined a traveling circus as a mechanic and married the teenage daughter of a carnival worker, Query writes.

“When Pee Wee told his new family about his escape, they all agreed that when the carnival returned to South Carolina, Pee wee would turn himself in and finish his sentence,” Query writes.

When he got out on his 18th birthday, Pee Wee found his new wife with another man and was informed that she divorced him.

“After that, he returned to Prospect and soon resumed his criminal behavior,” Query writes.

CATCHING UP TO HIS CRIMES

Crimes followed into Pee Wee’s adult life, including break-ins and stealing. The beginning of the end came when Pee Wee’s confidant Walter Neely was strong-armed by law enforcement into telling police where six people were buried, Query said.

North Charleston Police detectives had been trying to locate a missing teen girl and had zeroed in on Pee Wee as a suspect. Pee Wee had known the girl.

Neely led detectives to the shallow graves in Prospect, and all the victims had credible connections to Pee Wee, including the two brothers who were criminal associates, an ex-lover and her new boyfriend. (The missing teenager’s body was not among them, but Pee Wee eventually led law enforcement to her body.)

The additional murder-for-hire of the wealthy farmer was orchestrated by the farmer’s secretary and lover, Query said.

“I went to see him one-on-one in the Columbia Correctional Institute. He was entertaining and was cracking jokes,” Query recalls.

Rules for imposing the death penalty were changing at that time by the Supreme Court, and Pee Wee took full advantage, confessing to more than 20 total murders and leading authorities to more bodies. Additional life sentences were added to his record as more bodies piled up.

That is, until his final murder of another death row inmate.

“Rudolph Tyner robbed and shot an elderly couple who owned a store in Newberry, and he was on death row with Pee Wee,” Query said. “The couple’s adopted son was convinced the death penalty would never be carried out, so he hired Pee Wee to kill him. Pee Wee tried to poison him, but that didn’t work, so he smuggled some plastic explosives into prison and made a little supposed ‘walkie talkie’ and gave it to Rudolph.”

Pee Wee got the death penalty for the explosion on death row.

Confession before execution

“Pee Wee’s most poignant statement about his murders was, ‘I’ve been over every one of them in my mind, and I don’t see where I had any other choice,’” Query recalls. “He was trying to convince me that murder was perfectly reasonable.”

Asked whether he was sorry for anyone he had killed, Pee Wee said he always hated that he had to kill Jessie Judy, his ex-lover who was found in the shallow grave, Query said.

“During my last visit, he told me that maybe the judge was right, and he really wouldn’t ever stop killing people. He still maintained that his murder of Rudolph Tyner was ‘just’ and that he only did what the state intended to do but couldn’t seem to get done.”

Pee Wee was executed by the state of South Carolina on Sept. 6, 1991.

His last words before going to the electric chair were “Let’s get this done.”

Query, who still lives on Folly Beach, wrote two books about Pee Wee Gaskins’ life story. The novelized true crime series “Pee Wee Serial Killer or Homicidal Maniac” Volumes I and II can be purchased at Amazon and Barnes & Noble.